By: Robert Goodrich

Professor of History

Northern Michigan University

This is a continuation of the previous blog about the recently published Democracy in Crisis: Weimar Germany, 1929-1932. The previous post can be found here.

Alongside my overenthusiastic tendency to overdesign the game, the biggest conundrum proved to be the use of antisemitism, Nazi imagery, and playing a Nazi. These issues quickly became a stumbling block as the RTTP community split into roughly two camps. The first camp, to which I belong(ed), argued that this is RTTP. Our own name is “Reacting to the Past.” We do not shy away from historical controversies but instead believe that only by immersing ourselves in the intellectual realities of the past can we understand how history unfolded as it did without projecting our contemporary prejudices onto it. In short, antisemitism matters. Nazism matters. And we need to confront them head on using all the power of RTTP pedagogy.

The second camp did not disagree with any of this in the abstract. But practical application was different. They pointed out that there was, in fact, a red line that we should not cross, and that proactive use of antisemitic speech and Nazi imagery espoused by student characters were obviously on the other side of that line. A colleague pointed out the potentially disastrous public relations optics of a student using their phone to video a part of the game where a Nazi character spews antisemitic filth, captioned, “Professor Makes Students Be Nazis.” Twenty years of building a positive brand recognition gone in a flash… Other experienced instructors pointed out the dangers to the students. While we expect much of our students, asking, in particular, a Jewish student to either play a Nazi or be exposed to attacks by a Nazi character could well be expected to shut that student down, trigger warnings be damned. If the goal is to learn about these issues, placing such a high affective barrier is not necessarily conducive to that goal.

I am not about to try to weight how an individual student might respond emotionally to an RTTP character who embraces ideas diametrically opposed to their own beliefs, but we do this all the time. We expect fundamentalist Christians to be Darwinists, Muslims to play Crusaders, Blacks to play racists, Native Americans to be genocidal whites, and so forth.

And yet there emerged a particular sensitivity to antisemitism. Not that other game designers or the RTTP community in general were insensitive in the cases just listed. Far from out. I spoke with most of the designers of these games and they were keenly aware of the need to take the students’ sensitivities into consideration. They either developed various mechanics to isolate explosive content or they chose to remove it since, although relevant, it got in the way of bigger issues. And the visceral reaction of many faculty at the RTTP conferences when playing Democracy in Crisis kept appearing as the central point of concern in their assessments.

Here is not the place for an argument about why antisemitism proved a sort of last frontier. The fact is, it was. Game production stalled. The perceived stakes were high. But in 2022 the editorial board voted to advance it and UNC Press accepted it among its first tranche of RTTP publications released this year.

What happened? I think three things. First, there were changes in the RTTP board. New faces brought new perspectives, and there was a general shift towards advancing the game. But that just begs the question as to what had happened to shift general perspectives. While the game was regularly debated by RTTP, it played no role in board elections. So other factors were at play.

The second element was the consequences of the election of Donald Trump to the US presidency in 2016. This was not immediate, but the events of the “Unite the Right” rally in August 2017 and Trump’s persistent refusal to take a principled, consistent, and policy stance against racism (quite the contrary, in fact), were accompanied by an almost inevitable statistical rise in antisemitic and other racist acts and beliefs during his presidency. Whether Trump’s role was casual or contributory or correlative can be debated. And I have not done an opinion poll of RTTP members, but I noticed a distinct shift by 2017 in the willingness to grapple more aggressively with the controversial issues in Democracy.

“Unite the Right” Rally, Charlottesville, Va, 12 August 2017, by Anthony Crider

The third element flowed from the second. Working with colleagues, especially those who had faced similar design and classroom challenges, we made changes to how antisemitism and Nazi imagery were handled. The revisions specifically prohibited Nazi iconography (no swastika, “Heil Hitler”, fascist salute, or any such thing). Just as importantly, the section on antisemitism now allowed instructors to choose from three broad options on how to proceed with antisemitism.

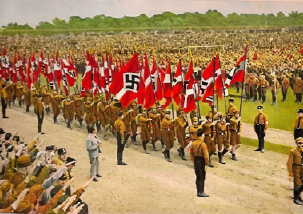

Reich Youth Rally, Potsdam, 1932 (photograph), Calvin University, German Propaganda Archive

1) Full integration: Antisemitism, as essential to the period and the issues, remains since leaving it out sanitizes the Nazis, and it is the rise of the Nazis that is the primary reason we study Weimar Germany. It must be confronted head on, and that includes exposing how an overtly racist organization can twist its rhetoric to fit into the norms of a democracy.

2) Full exclusion: It is dropped as a debate issue entirely. While antisemitism was an integrating construct for the Nazis, they rose to power based on other issues – unemployment, opposition to Versailles, anti-Marxism, collapse of traditional values and ways of life, etc. The game, and history up to 1933, make sense without antisemitism (what happens after, however, does not). After all, this is not a game about the origins of the Holocaust or about the Nazis or Hitler. The topic is replaced by racial eugenics (race hygiene) and eugenic sterilization, which gets at the broader issue of Nazi racial thinking.

3) Hybrid: Antisemitism remains in the game but rather than having players express those ideas in character, we use historical documents from ~1930 to be read by everyone, distributed in place of speeches by antisemitic characters.

The revisions went a long way towards allaying lingering concerns, but the changed and charged political climate was likely decisive.

About the Author

Robert Goodrich’s research interests lie in Modern Central European history with a broad and integrative approach. His research and teaching emphasizes cultural and social history and the interplay of factors such as labor, gender, sexuality, and religion in identity construction. The nature of his research into religion and identity also requires a comparative view of European and American experiences, reflected in his interest in transnational history and recent focus on questions of identity related to Austro-Hungarian migration to, from, and through Michigan. Goodrich also works to promote internationalization at Northern Michigan University and has taken students to Spain, Peru, Greece, and most regularly, to Austria.

Blog Author Questionnaire

One word to describe faculty: Engaged

Two words to describe (your) school: Supportive, Humane

Three words to describe students: Kind, Underprepared, Distracted

Four words to describe favorite games: Team-Based, Open-Ended, Immersive, Problem-Solving

Five words to describe Reacting: Contingent, Document-Based, Confrontational, Student-Centered, In-Depth