Reacting to Mark Carnes with Gratitude

A Tribute and Brief History from the Reacting Membership Committee

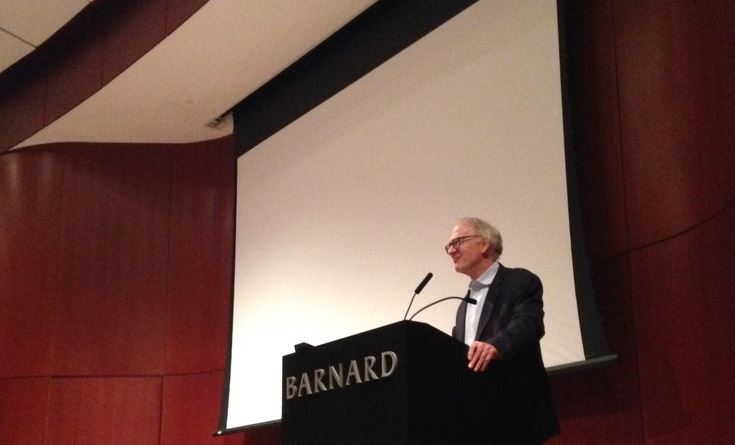

In the fall of 1996, Mark Carnes, a history professor at Barnard College, restructured his “Great Books” seminar as a set of debates. During the second such debate, set in Ming China, two plucky students—playing the role of the Emperor and “his” top adviser—managed to take control of the class.

As the focus of the class shifted from the instructor to the student leaders, the entire class became passionate and engaged. Mark had never seen anything like it.

He wondered: Might this be the “Holy Grail” of higher education pedagogy? Students teaching themselves? But he puzzled over a conundrum: How could students, who don’t know the material, “run” a college-level class? The answer, he concluded, was to regard a course as if it were a mansion, with each room designed and furnished with rich content. Students would learn the content by inhabiting and exploring the mansion. And they would be drawn into the mansion through the motivational power of games and make-believe, supplemented with enticing liminal elements. Barnard’s new president, Judith Shapiro, an anthropologist, embraced the concept and encouraged Mark to experiment. He did so during the next few years.

A few grants and multiple consultations with scholars later, a handful of new history games were being developed. Within the next few years, an emerging core of several dozen faculty embraced Reacting with special zeal. In 2004, Reacting won the Theodore Hesburgh Award (TIAA-CREF) as the outstanding pedagogical innovation in the nation; publicity for the award further facilitated early dissemination of the program. Eventually, a team of scientists applied for and received a grant from the NSF to develop and assess other Reacting games in the history of science. Reacting moved into the realms of English literature and art history.

By 2006 the Reacting community had grown to include several hundred faculty and administrators. They brought a wealth of ideas that transformed Mark’s original concept into a rapidly growing pedagogical system.

The spread of Reacting resulted in the proliferation of new games, and an editorial board to oversee their development. Games were published--first by Pearson, then by W.W. Norton, and now by the University of North Carolina Press.

From the start, Reacting spread by word of mouth, via publicity about Reacting; through articles in higher education publications and awards conference presentations; and on social media. Reactors began to meet yearly at the Annual Institute, the Game Development Conference, the Winter Conference, and at regional workshops.

Former students of Mark’s, now professors themselves, got involved. Reacting has entered high schools, prisons, and senior centers. It has appeared in Canada, China, Norway, Australia, New Zealand, Egypt, Hong Kong, South Korea, Switzerland, France, Denmark, Spain, and Israel.

Undergraduate students were the impetus for Reacting, and they have been some of its best participants, sounding boards, and shepherds.

Nearly all game designers have received substantial feedback from students; often this includes detailed suggestions on how to shape roles and rules. Undergraduates have also played a major role in organizing and running faculty training workshops. The importance of undergraduates was recognized by the Reacting Board, which included two voting undergraduate members almost from its inception.

Reacting has grown because of the extraordinary (and almost entirely unpaid) activities of hundreds of volunteers. Mark was and remains “boggled” by this outpouring of voluntarism. But those of us who know Mark, have worked with him, haggled with him, dreamed along with him, and look forward to continuing this almost magical thing he has created are aware of the debt we owe to him and to his innovative response to a mid-career teaching crisis.

Thank you, Mark, from all of us involved in Reacting.

.

.